When Ram appeared before us all helobaba.com

The family home of producer-director-writer Moti Sagar, a bungalow nestled in a leafy cul-de-sac of Juhu, has had a few news crew visits in the past couple of weeks. Sagar, the son of Ramanand Sagar, the man who midwifed an unprecedented Ram consciousness in India through his serialised Ramayan in Doordarshan starting in 1987, asks me, “Do you want the story of Ramanand or the story of Ramayan?” He asks me. I’m there for both, I say.

“When did the interest in Ramayan go away anyway?” he tells me, almost bemused. It appears Ramanand Sagar, a Kashmiri Punjabi brought up in Lahore, had a lot on his mind when he decided to script and film the epic for television—and none of it had to do with a symbolic divine resurrection.

But first, jump cut to April 2020. The pandemic’s devastation was unfurling at a ferocious pace, when the government-run Doordarshan revived airing Ramayan again, prompting the then minister of information and broadcasting Prakash Javadekar to tweet a picture of himself relaxing on his sofa: “I am watching Ramayana, are you?” He had to delete the tweet soon after, following a wave of indignation for writing about watching a show in the midst of a wave of migrant workers returning home following the announcement of the first lockdown.

As soon as the re-run began on March 27, Doordarshan’s viewership rose exponentially. From nine million in the second half of January, it went to 545 million in the last week of March. A few months later, Shemaroo TV announced that the mythological show would begin airing on July 3 on their channel. It continues to stream there.

Sagar said that the “Prime Minister’s Office” got in touch with them for reruns of all their mythologies, including Luv-Kush and Shri Krishna. On the morning of May 2, 2022, DD National tweeted: “Thanks to all our viewers!! #RAMAYAN – WORLD RECORD!! Highest Viewed Entertainment Program Globally.” The accompanying video stated that the April 16 telecast of the mythological show was watched by 77 million viewers worldwide, making it the most-viewed episode of TV ever. An infographic compared Ramayan with Game of Thrones (17.4 million) and The Big Bang Theory (18 million).

Mint reported in the days following this tweet that the final episode of the classic American series M*A*S*H (“Goodbye, Farewell and Amen”), on February 28, 1983, had, in fact, notched up nearly 106 million viewers. But leading up to the Ram temple consecration in Ayodhya on January 20, for which, Sagar tells me, his family has an invitation, the Sagar family is fielding a lot of questions again, with new fervour. One TV crew asked Sagar if they could photograph him with an imposing portrait of the PM in the background. Sagar replied he usually took his portraits standing beside an idol of Krishna, which has been in his family for a long time.

Ramayan was made at a time when Doordarshan was the only option for Indian TV viewers. It’s possible that somewhere in its initial run — when the telecasts would bring the nation to a standstill and around 100 million viewers were said to watch each episode — it came close to, or maybe even crossed the M*A*S*H* record. Various estimates suggest that around 65 crore people watched the show in its original run. The television revolution was well on its way in the 1980s. Screenwriting and directorial talents from the margins of Hindi cinema — then in the throes of Bacchanalia — found an offbeat creative cradle in Doordarshan.

In 1983, India produced 800,000 TV sets; by 1986, 3 million. This was a revolution with a long-lasting psychological impact. In their book Who Moved My Vote (2023), Yugank Goyal and Arun Kaushik write, “The normative understanding of Indianness as one nation (Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities come to mind), and one way of thinking was triggered, and in a big way, constructed by television penetration in India.” On these prime-time stories, we watched history, life, politics and Indianness converge. Serials like Bharat Ek Khoj, Hum Log, Buniyaad, Tamas, Yatra, Hum Hindustani and several others constructed a post-Independence India. However, several television columnists and books on Indian television point out that during the Doordarshan heydays of the 1980s, large sections of TV viewers felt their needs and aspirations were not represented in TV serials. And yet, as only technology can often achieve, the value judgments, traditions and customs appearing on TV were slowly acquiring the status of uniformity.

This was the backdrop against which Ramanad Sagar’s Ramayan erupted on our Onidas, Upturns, Dyanoras and Westons. At 9.30 am on Sundays, life came to a standstill. Breakfast became early or hurried, and roads were emptied. Conversations around lunch often included what ensued between Ram and Dasharath or how Sita had aced the yellow-and-red satin sari. Viewers garlanded television sets and the newspapers. The first attempts at visual effects had enough novelty—including a soaring Hanuman with the Dronagiri mountain perched on one of his hands, a resplendent rotating wheel behind the head of divine beings, or a shaft of conical shimmery light emanating from blessing hands.

Ramayan was first televised in January 1987, when there was just one television channel in the country. The idea of serialising a Hindu epic came from SS Gill, the secretary of information and broadcasting at the time. Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi had hesitated to accept his proposal, fearing that the show was meant for a mainly Hindu audience. Sagar recalls that the idea for creating Ramayana for the screen was an old wish of his father, who was a devout Hindu. “He used to have Ramayan Katha at home with a closed circle of friends at our home on Sundays. His interest in Ramayan had nothing to do with any political ideology. He was not interested in Ram as divinity but as the beacon of “Maryada Purushottam”—or the moral or ethical exemplar of a man. In fact, the seed of creating it for Doordarshan had come to him much earlier, from Morarji Desai.”

Sagar, who assisted his father through the scripting of the episodes and filming it on a hugely mounted set by then popular set designer Hira Bhai Patel at Umargaon, a town bordering Maharashtra and Gujarat, said, “We assimilated elements from various Ramayan. We read 30 different Ramayan before deciding on what we wanted to include from which version.” Doordarshan commissioned the show, and Colgate came on board as a sponsor. “The budget was around ₹9 lakh per episode,” says Sagar.

AK Ramanujam’s essay, ‘Three Hundred Ramayanas’ which was written for a conference to be held in 1987, the same year as the Ramayan broadcast began, shows the Ramayana’s various tellings across Asian societies over 2,500 years. He, together with other scholars of Hinduism claimed that there is no singular version of the epic. Sagar says his father created his show in this spirit—a synthesis of various moral prisms, sub-plots and charactorial nuances.

Ramanand Sagar was born in 1917 to a Punjabi family in Kashmir. After his mother died and his father remarried, his maternal grandmother who lived in Lahore decided to bring him up. Sagar went on to study Urdu and Persian at Lahore University before becoming a journalist, columnist and essayist. After he got acute tuberculosis and miraculously recovered from it, and his father brought him back to Kashmir, Sagar became an editor of the newspaper Daily Milaap. After Partition, he brought his maternal family to Delhi and settled there, continuing to write. He moved to Bombay to try scriptwriting in the emerging Hindi film industry a few years later. Sagar went on to write SS Vasan’s Insaniyat (1955) with Dev Anand in the lead, and Paigham (1955) with Dilip Kumar in the lead, also directed by Vasan. He wrote, directed and produced Ghunghat (1960) with Bina Rai, Asha Parekh, Pradeep Kumar, Bharat Bhushan and Rehman in main roles, which became a super hit. In Doordarshan, his serials Dada Dadi ki Kahani (1986) and Bikram Aur Betaal (1985) saw successful releases before he scripted television history with Ramayan in 1987.

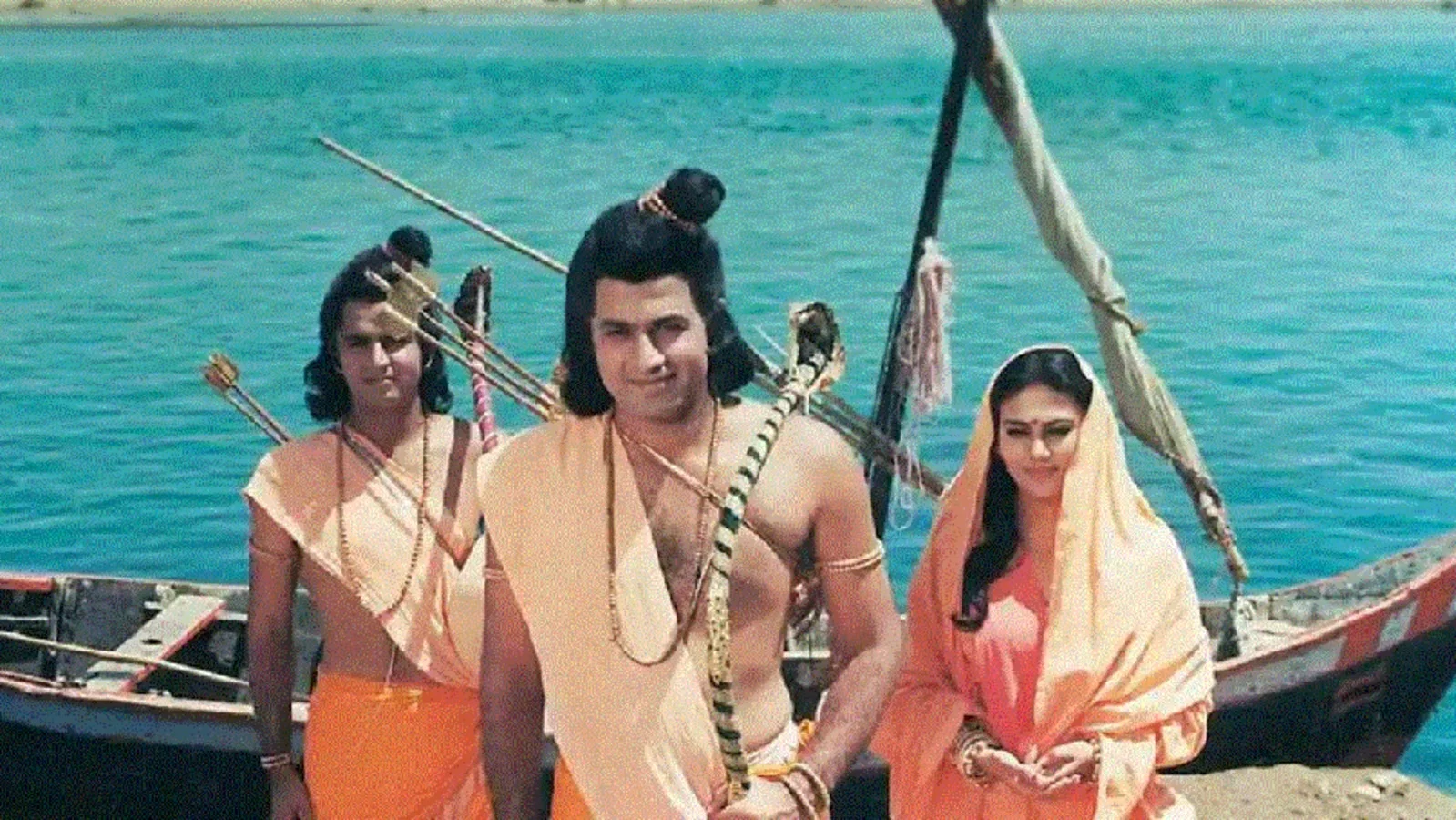

The show ended in July 1988. Govil, and Deepika Chikhaliya (who is still a member of Parliament of the Bharatiya Janata Party), played the lead roles of Ram and Sita. Until June 2003, the show was featured in Limca Book of Records as “the most-watched mythological serial in the world”. While stories of devout Hindu ladies worshipping their television sets on Sunday mornings became pre-Internet viral, there are some accounts of effusive non-Hindu fans of the serial too. In her book Telly-Guillotined, Amrita Shah talks about a Christian lady writing to one of the characters, “May our Lord Jesus and Mother Mary Bless you and keep you well,” and a gushing Muslim fan writing in a letter to Ramanand Sagar, “Your name will shine and shine like the morning star in the horizon.”

In his book Politics After Television (Cambridge, 2001), which examines Ramanand Sagar’s Ramayan, Arvind Rajagopal, professor of media studies at New York University, shows that the BJP gained big from this escalating, collective febrility over an epic originally believed to have been written by the sage Valmiki approximately around 200 B.C.E, and recreated for the screen with a thriller-like denouement. He writes, “Somehow, when BJP was gaining ground, people received a sentimental religious dose every week, through 1987–88 in the form of Ramayan, and between 1988–90 through Mahabharata, which also drew a massive following (second only to Ramayan). This interweaving of political-real and religious-reel during 1987–90 provided a powerful recipe to mobilise the voters ’minds into looking at BJP as a party that carries the emotions of India.”

In Sagar’s words, his father had inadvertently managed to awaken “a sleeping giant”.

In an email interview, Rajagopal tells me, “In Politics After Television, I showed that the Ramayan serial broadcast in the late 1980s was hugely popular across all divides. Although the Congress authorised the broadcast, the BJP stole the benefit, thanks to the Ramayan serial, and the alignment of its political stars (business classes ready to back a more business-friendly party, and so on). I also showed that even if television was the catalyst, the interaction of the Hindi press and the English press explains a great deal about how the BJP was able to turn the tables on the Congress, which had appeared invincible as recently as 1984.” He emphasises that Ramanand Sagar was careful not to assert Hindu supremacy, but it provided ammunition for the BJP’s interest in rendering “Hindu” into a political identity. “It did so simply by virtue of the mass popularity of the serial, on a scale that had never before been witnessed. …The resonance of symbols and stories like the Ramayan is really on another level from that of most cultural texts, due to the far greater extent of its percolation across languages and dialects, and over many more centuries, compared to other texts. So its relevance and uptake are not a surprise. What is new is the extent to which the epic is being used to set the collective sights of society: the Ram mandir in Ayodhya.”

The question that’s on Moti Sagar’s mind too, is: “With the Ram temple, will a television Ramayan still retain its appeal, or now that the temple will exist, will we witness a new, much more politicised Ramayan frenzy?” He says that his 30-plus years of experience as a television and film producer-director can’t offer him a definitive answer yet.